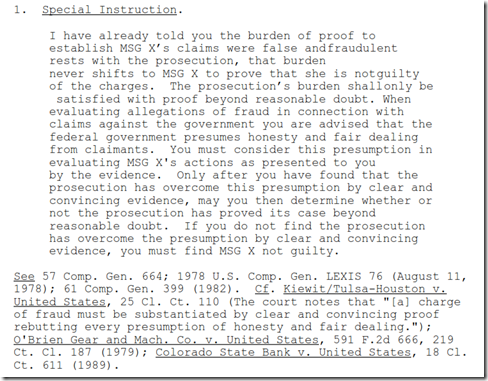

From time to time I find a need to ask for a special instruction or a rewording of a BB instruction. Here is a favorite, in BAH/TAD/TDY fraud cases:

I have asked for (but not gotten) a “Consciousness of Innocence,” instruction in cases where there is evidence to support it (cooperating with NCIS, giving a full statement, consenting to searches, other assistance. A one point I was also of the opinion that a willingness to take a polygraph examination was also indicative.). I craft it based on the prosecution friendly consciousness of guilt instruction. There appears to be acceptance in some courts of this instruction.

Federal Evidence Review continues the practice of checking it twice for federal jury instructions among the circuits. Personally I have found the Eleventh’s instruction for child por******phy cases to be an excellent resource.

Court-Martial Trial Practice Blog

Court-Martial Trial Practice Blog