Many years ago we sought to improve our counsel performance at NLSO Norfolk with developing checklists, protocols, and a PQS system. It seemed to work.

Now here is an article, Darryl K. Brown, Defense Counsel, Trial Judges, and Evidence Protocols, Brown, Darryl K., Defense Counsel, Trial Judges, and Evidence Protocols, Texas Tech Law Review, Vol. 45, No. 1, 2012; Virginia Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper, 2012-70. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2181301. The author

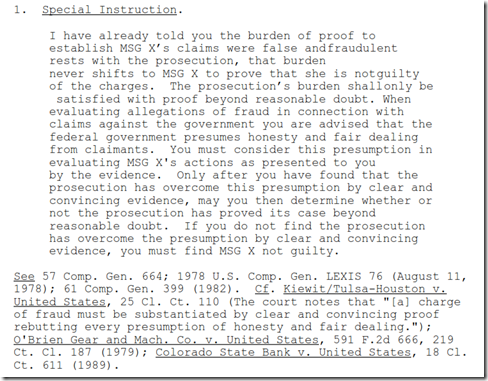

argues that constitutional criminal adjudication provisions are fruitfully viewed not primarily as defendant rights but as procedural components that, when employed, maximize the odds that adversarial adjudication will succeed in its various goals, notably accurate judgments. On this view, the state has an interest in how those procedural mechanisms, especially regarding fact investigation and evidence gathering, are invoked or implemented. Deficient attorney performance, on this view, can be taken as a problem of the state’s adversarial adjudication process, for which public officials – notably judges, whose judgments depend on that process – should assume greater responsibility. The essay briefly sketches how judicial responsibility for the integrity of criminal judgments is minimized in various Sixth Amendment doctrines and aspects of adversarial practice. Then, instead of looking to Sixth Amendment doctrine to enforce minimal standards for attorney performance, the essay suggests that judges could improve routine adversarial process through modest steps to more closely supervise attorneys’ performance without infringing their professional discretion or adversarial role. One such step involves use of protocols, or checklists, through which judges would have attorneys confirm that they have performed some of their tasks essential to adversarial adjudication, such as fact investigation, before the court would rely on their performance to reach a judgment, whether through plea bargaining or trial.

Court-Martial Trial Practice Blog

Court-Martial Trial Practice Blog